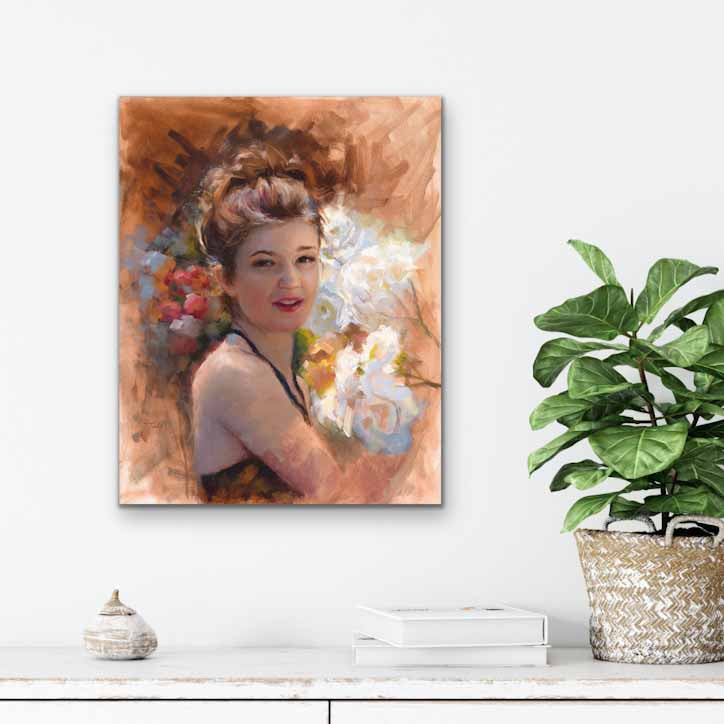

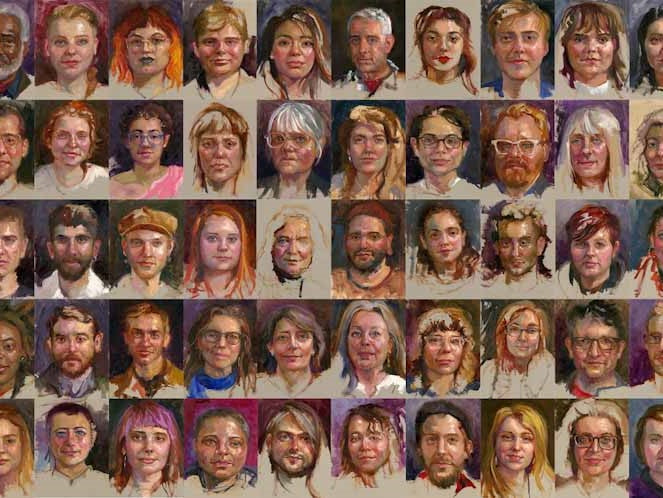

Continued from 51 Oil portraits from life: Community Remains part 3, the intuitive slow art of seeing

The more you look the more you see

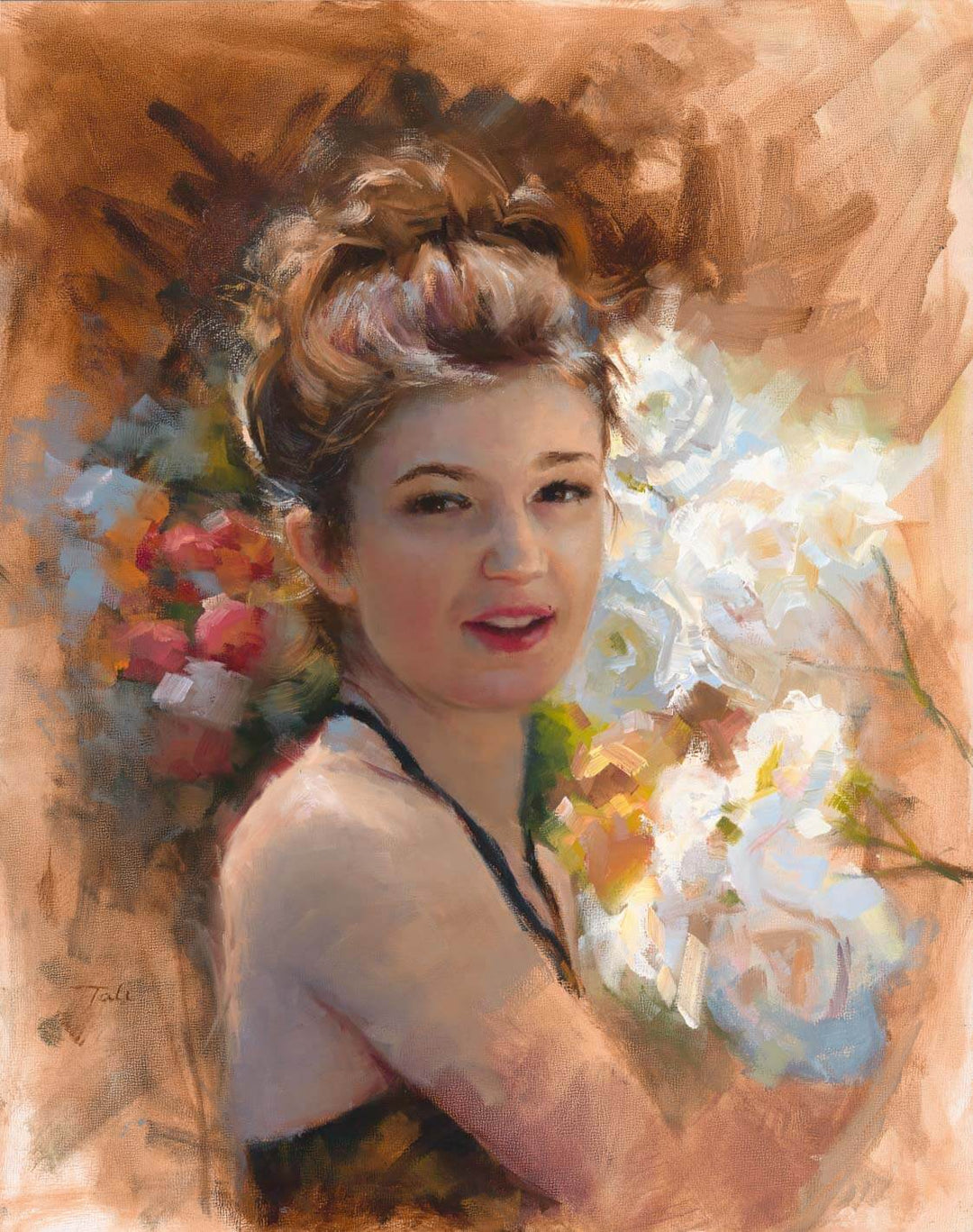

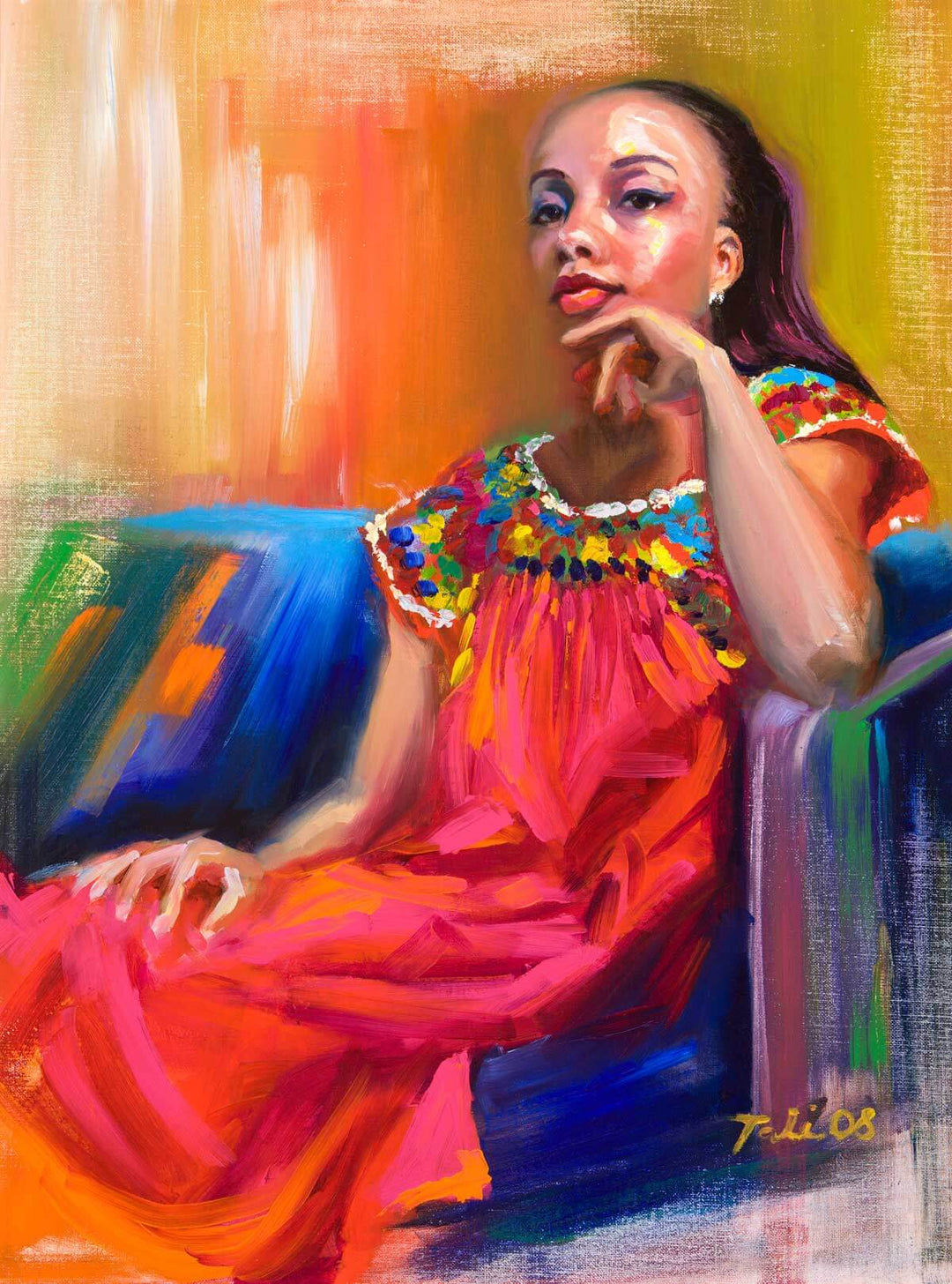

In retrospect, it has been naive of me, a regular portrait painter, to not consider the close relationship between portraiture, identity politics, and feminist art. At their core, portraits are a form of identity art. My own perspective as a female artist alone, greatly influenced both my perception of the and expression of the artist identity, as well as the portrait likeness. Much to my surprise, there was a marked difference between my interaction and even final painting with my sitters depending on their own identities. Achieving a realistic portrait proved to be a psychological challenge as well as a skilled one.

It isn't something that is easy to discuss or express, but despite all my egalitarian values, I found myself responding differently to my sitter depending on their looks, and associated identities. This difference if evident, at least for me, in the finished portrait painting.

All my sitters were artists themselves. They all found meaning and strength in expressing their artist's identity and through visual art. Once that commonality was realized in the painting session, I found the experience far more relaxed and therapeutic for both of us.

Other portrait painters note this observation, reading of Rose Frantzen's experience had somewhat prepared me for the personal challenges I might discover through conversations. "As I listened to people tell their stories, I learned that certain hardships can limit people's possibilities . . . I learned about tragedies all over town that I didn't know anything about" (40-42). I found myself questioning the relationship between artists in particular and significant life challenges.

The following are some other general observations I made through conversation and the written questionnaire answers from my sitters.

Most of the people I painted were not religiously affiliated, though many considered themselves spiritual. They tended to lean left politically, though there were several centrists, and possibly one closeted conservative.

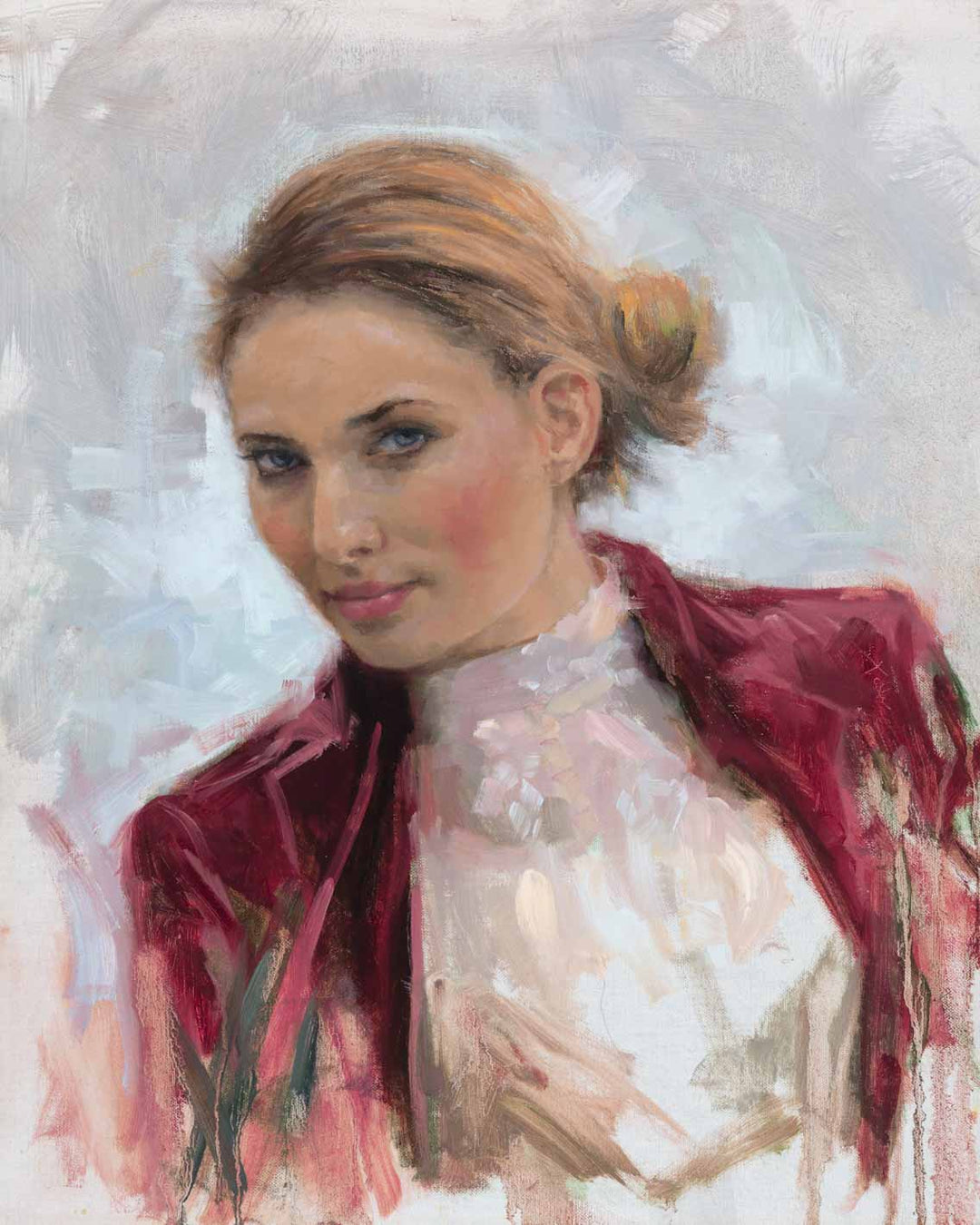

Three to four people were very open and accepting of their gender fluidity. I found difficulty in painting them trustIng my personal perception and not leaning on constructs of social identity for predetermined aesthetic stereotypes.

My portrait sitters were also surprisingly mostly working class or had come from working class families. I know of only one out of my eighteen student graduating cohort that was ever reliant on a trust fund, though I suspect a few others.

In my experience, the religious and social class tendencies I witnessed are on the other side of the spectrum I previously noticed in artists working outside of formal academic communities, especially amongst my group of women artists. Before attending college, my general impressions of artists and craftspeople was that they were more religiously affiliated, conservative, and generally at least middle class. This is likely due to my style preference in art toward more representational or figurative artistic work. While my experience is obviously biased, it's an observation I believe worth noting, and certainly has broadened my perception of the identity of makers, or at the very least how craftspeople frame their identities.

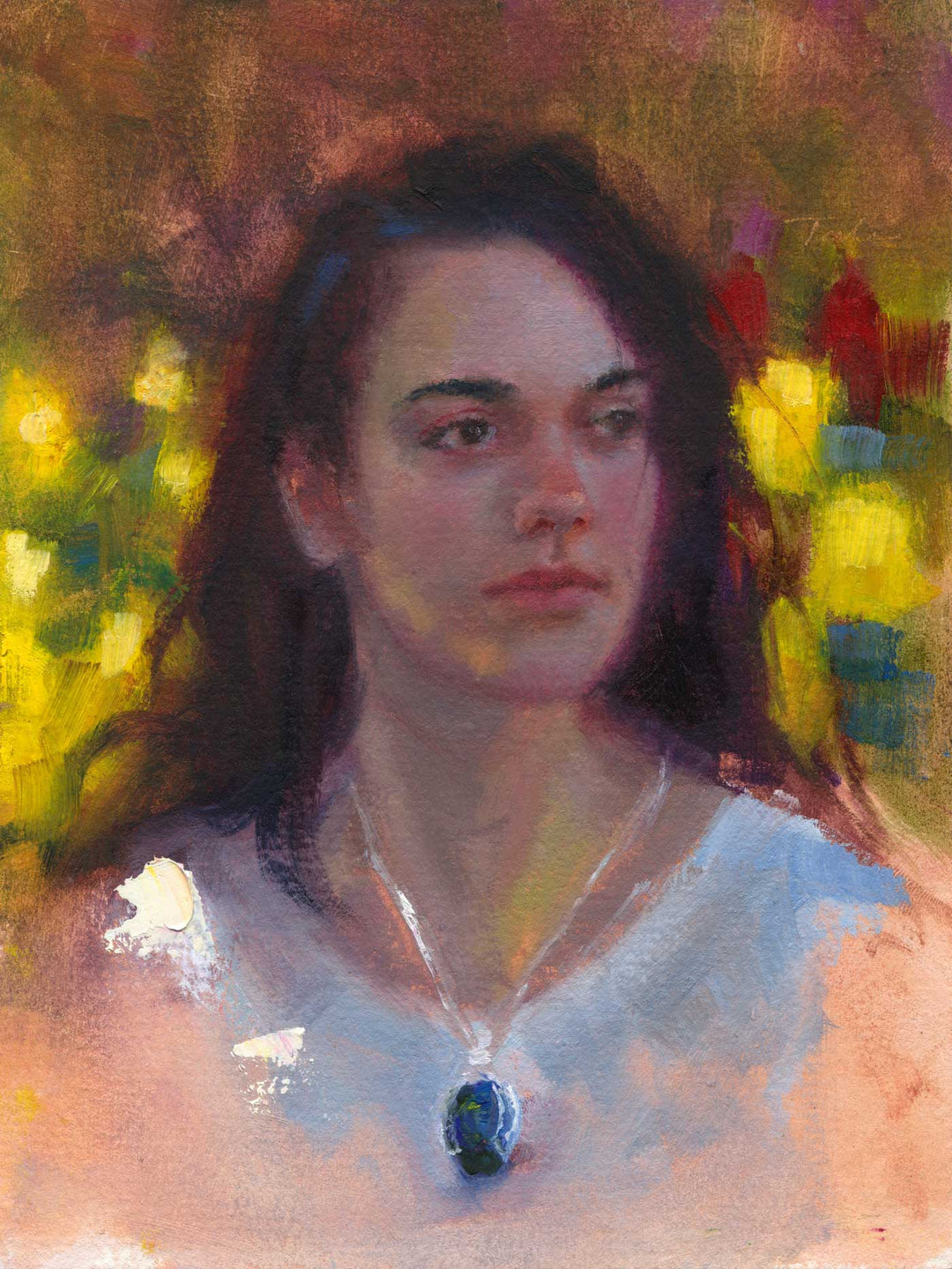

The top reasons listed for subjects wanting to have their portrait painted are that they wanted to help me with my project and participate in both my painting process and the community. Several people were curious regarding the experience because they had never had their portrait painted before, let alone painted from life. I found the latter amusing since I was drawing from a community of artists and thought the experience of modeling for painting or drawing was ubiquitous to being an art student, and certainly an art history professor or scholar. There was a person or two or who confessed they simply wanted a free painted portrait of themselves. This specific group of people was a little more difficult for me to work with, as I couldn't fully relax into the experience not being able to shake the feeling I was being used or commodified. But it wasn't just the idea of being commodified that bothered me, after all, my recent works with portrait commissions commodification of my time and this art form is a given. I believe it was the the conversation with these subjects were far more one-sided. Rose Frantzen's words echo my experience, "Everything was proper, little was offered, and everything I asked was deflected back toward me . . . By the end of the day the inside of my head felt all scratched up" (37).

At times the process of video recording each session felt like it was interfering with my goal of understanding and seeing the true identity of my sitters. There were times where I felt we were both on exhibition, as if we were unwilling participants in some sort of performance art. When the documentation interfered with our experience, I didn't hesitate to simply turn off the camera since video photography was not an integral component of this art project.

Most of my sitters liked their own faces and accepted their perceived physical imperfections. Most of them liked their portraits and felt I had captured varying degrees of their likeness, though very few felt I "nailed" their exact likeness. The few people who didn't particularly like their faces, also didn't particularly like their portraits.

There were a handful sitters that were surprised by seeing themselves beautiful through their painted portrait. These were fewer than I hoped for and must admit I am disappointed in myself for not being able to better express the beauty I saw in them. Two sitters politely requested that I change their portrait and one asked that I not touch it further after the initial sitting. I was happy to oblige and eager to create something they would want or cherish.

Many of my sitters didn't wear makeup or anything particularly special, clothing or accessory-wise, stating they wanted to be "real" with me. I found this of some interest. Rose Franzen made her sitters wash their faces. "I hate to paint faces that are all covered up . . . the skin . . . loses its vibrancy" (36). While I too struggled to find people under their masks, I deeply appreciate a few sitters who wore something special for the occasion: lipstick, sentimental jewelry, favorite shirt, a complicated plaid just to trip me up. I even had a couple people express that they toned down their more painted-up looks, so that I would have an easier time painting their portrait. The varying considerations gave me a broad experience sampling of practicing my craft, which was welcome. I was careful to always include facial jewelry in the portraits, time permitting, feeling it was a more intimate expression of self from the sitter.

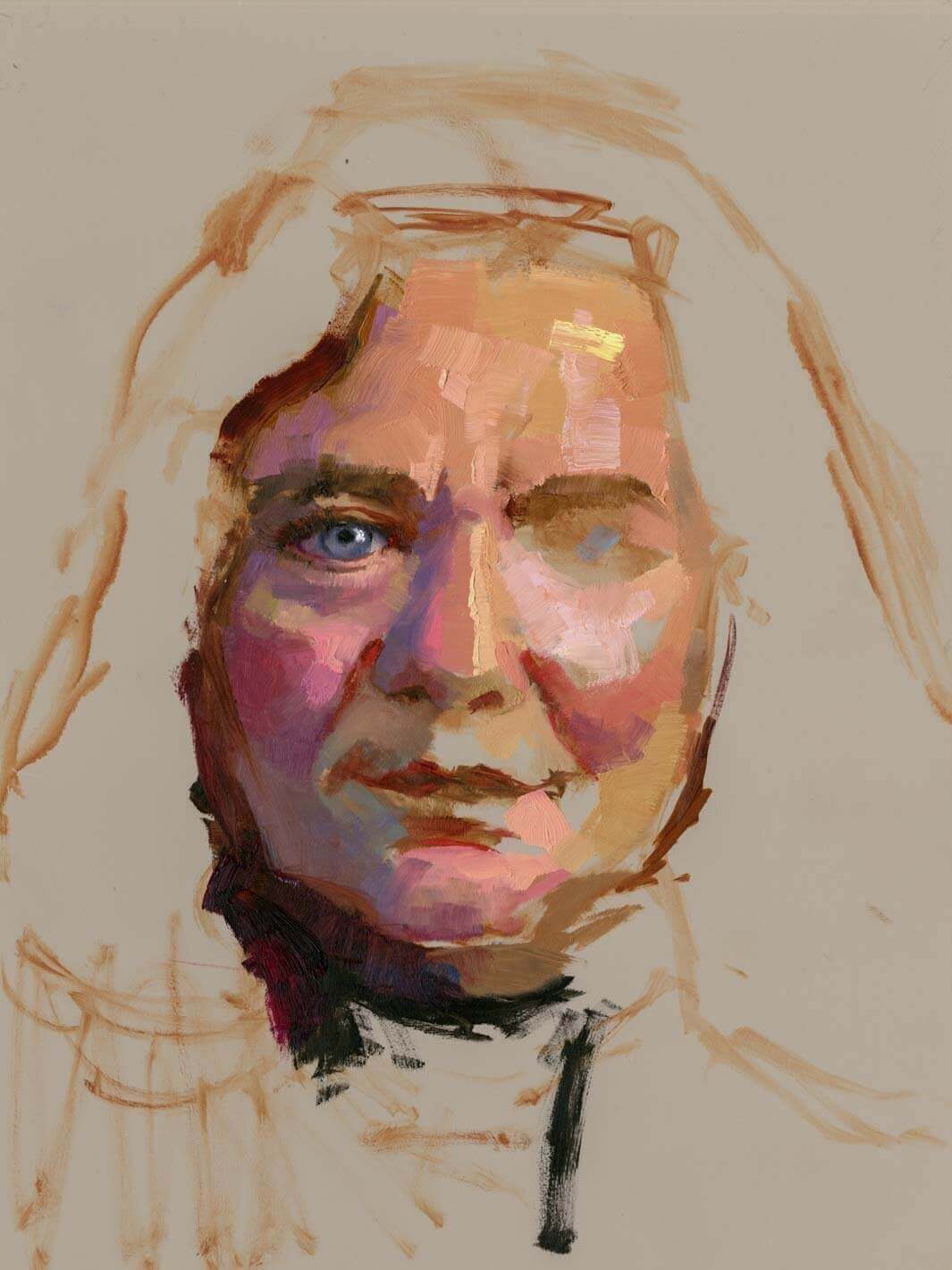

The questions of wearing spectacles came up quite a bit in the portrait sessions. In general, painting someone wearing glasses is considerably more challenging than painting them without glasses. It isn't the frames themselves that make it a challenge but the actual prescription of the eyewear that distorts facial features that can be problematic. However, people who always wear glasses rather than just on occasion or as an accessory, can be difficult to identify even for their closest loved ones without their glasses. I left the choice up to the sitters and gave myself a little more time after our painting session to those who felt their eyeglasses were an essential part of their looks or identity.

Know Thyself

Eyesight and identity were also the driving force behind the imagery my own portrait (number 17), which is noticeably less "finished" than any other in the series. In the self portrait, the left side of my face is left fairly undeveloped. My left eye socket is mostly blank with a single brush stroke of light-blue gray indicating placement for the iris.

The session painting myself was a left-over session: one of my sitters didn't show up, and after waiting forty-five minutes I started painting myself from a picture on my iPad. Since my time was limited, and I was working from a still photo of a familiar subject, I deliberately used a different strategy for the portrait. I chose to just render just one or two features, but with far more precision, than my typical "sneaking up" approach facilitated. I focused on my right eye and brow. I became fascinated with the new folds my middle-aged face was acquiring, noticing for the first time I was developing dark "bags" under my eyes, as opposed to the happy crow's feet I admire so much in older adults. In this realization I found a certain relief in shedding the pressure of making myself beautiful, or even creating a beautiful painting.

When my time ended, I thought I would return to the painting the next day. But as the days passed, I grew accustomed to my one-eyed face looking back at me. The expression was slightly less benevolent than the other painted faces around me, but it was accepting. The missing eye became an inner eye, symbolizing both insight and quite literally a deteriorating eyesight. My right eye contrasting significantly became the artist's eye, both calculating and creative, forever aware and open to new experience, and closely associated with my more contemporary identity.

Works Cited

Frantzen, Rose. Portrait of Maquoketa. Old City Hall Press, 2009. Portrait of Maquoketa information and book available here.

Leave a comment