Community Remains: A Thesis Presented to the Oregon College of Art and Craft and Pacific Northwest College of Art

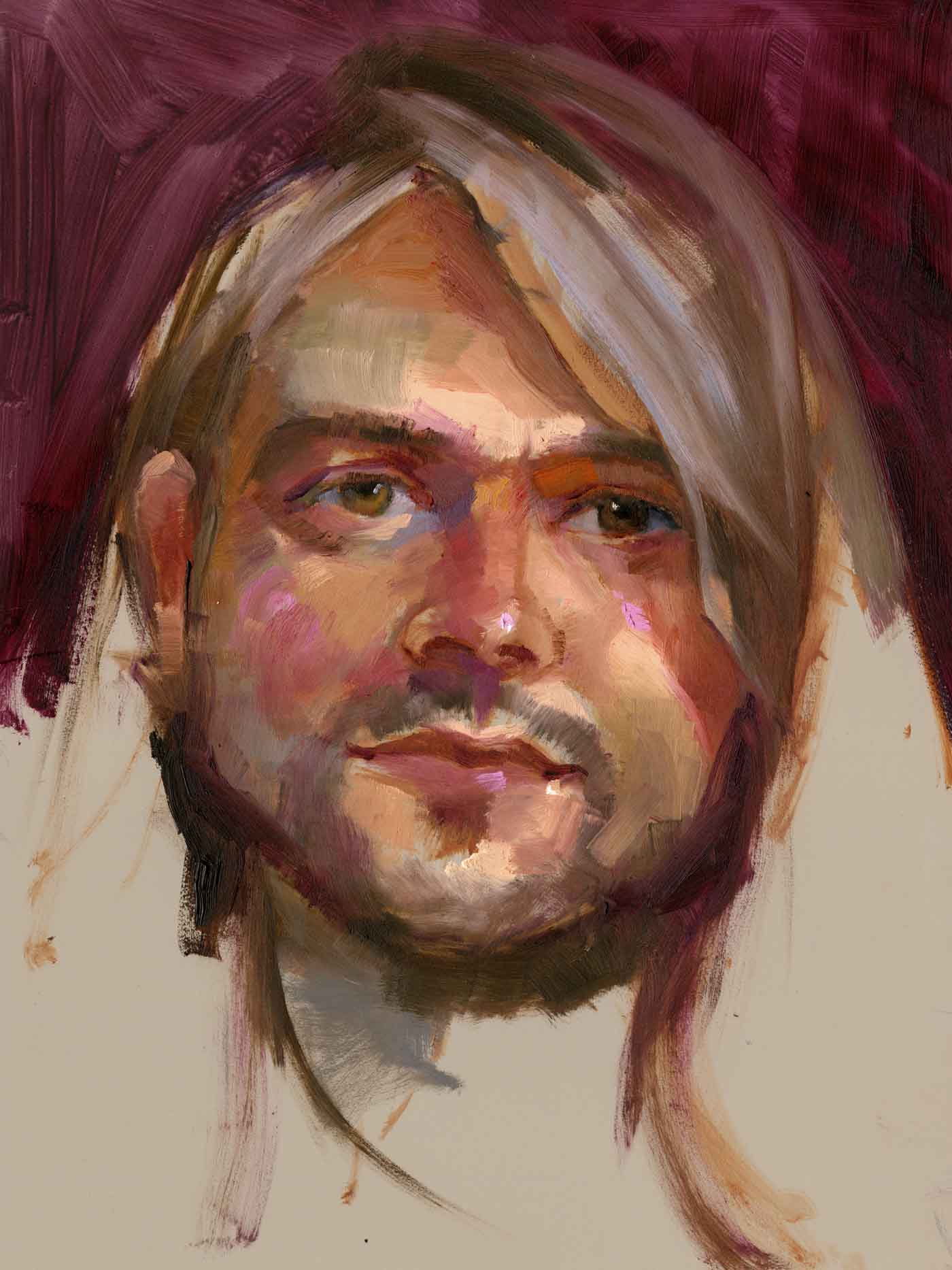

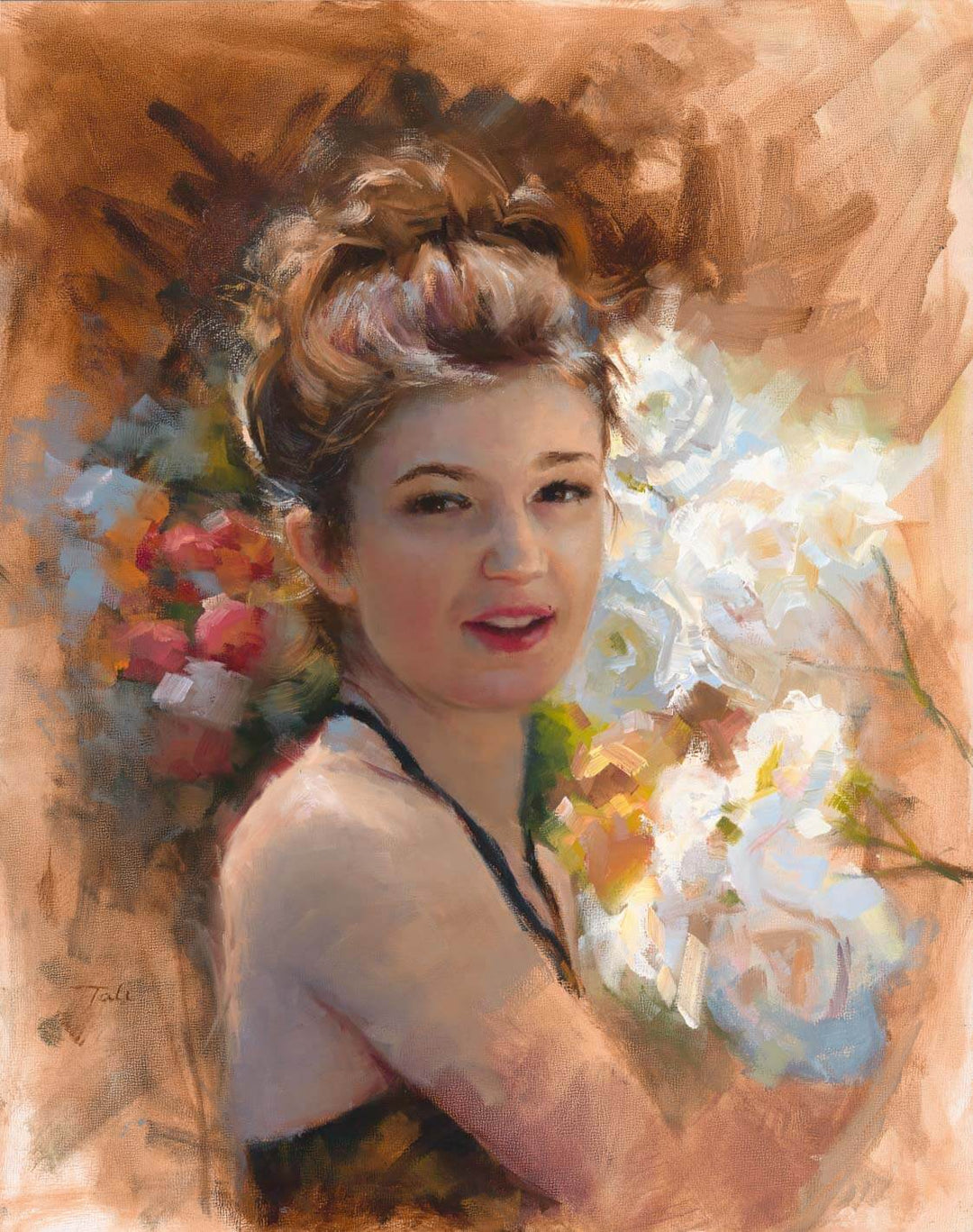

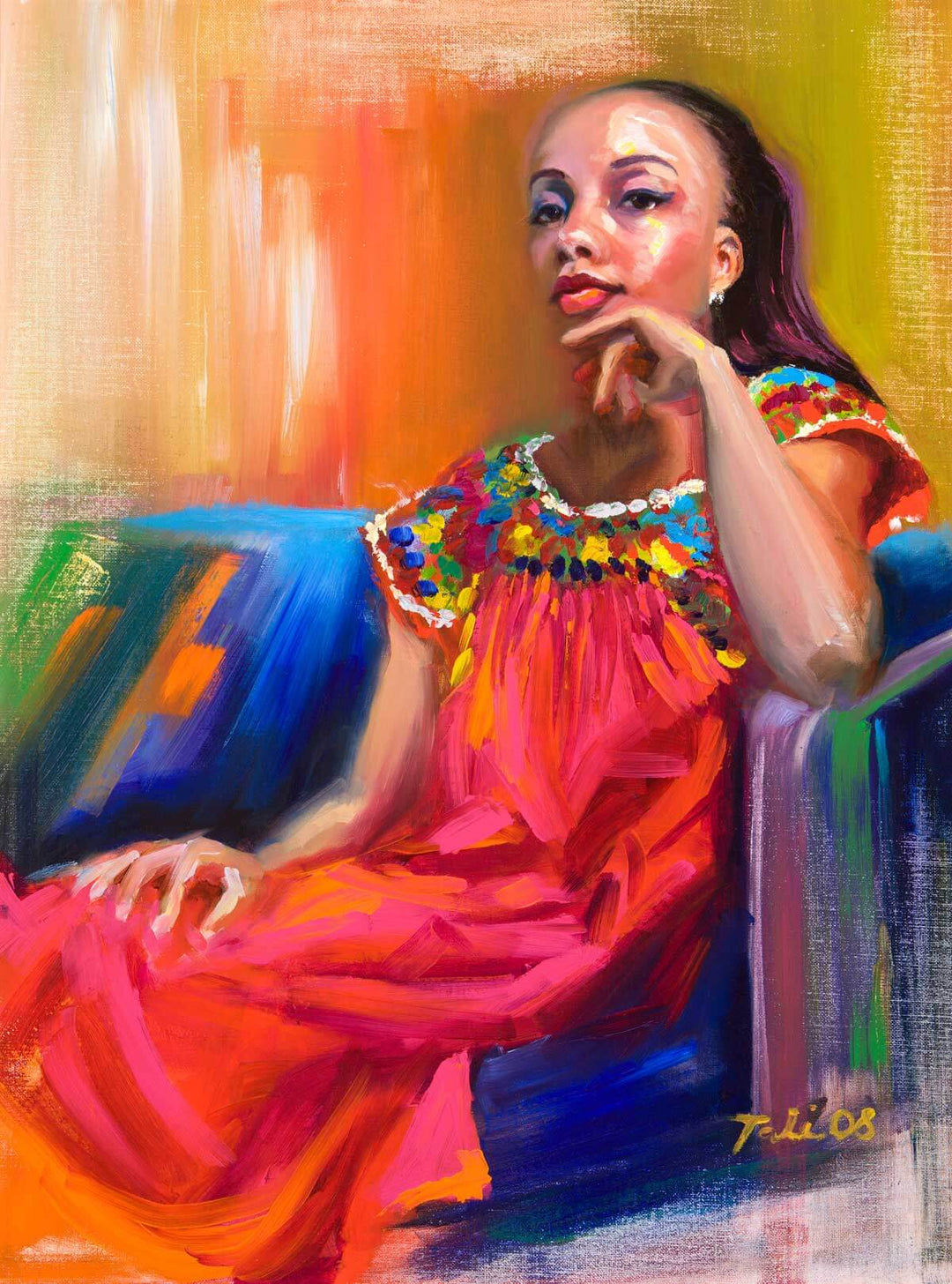

In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Bachelor of Fine Arts. Talya Johnson May 7, 2020. Approved for the Drawing and Painting Major by Abby McGehee, Thesis Advisor and Committee Members Lee Stewart and Michelle Ross.

Revised from original for clarity, length, privacy, and readability.

In loving memory of my mother, Connie Rodgers, who gave me the love of learning, painting, and writing, despite herself.

This work is dedicated to those at Portland Community College and

Oregon College of Art and Craft who put up with my pride and stubbornness and taught me what art means, despite myself.

I’m so grateful to my father, Neal Martin, who never stopped believing in my art, and the Ford Family Foundation that made my education possible. Most of all my deep gratitude goes to my soulmate, Troy Johnson, and our four sons Teddy, Tommy, Lawrence, and Sammy who never ceased to support my dream of earning a Bachelor of Fine Arts. You are my world and my meaning.

Part one: commencement of a dream

The death of the realistic portrait

"How do I read a portrait of someone I don't know?" The question from a member of my fellow artist made me stop in my tracks. A thousand other questions collided with the impenetrable brick wall this tiny query presented. In an age inundated with an overwhelming bombardment of imagery, what is the relevance of the painted portrait?

One of the first things I encountered in art school was a resistance to representational figurative art. Photography, even portrait photography seemed acceptable, and figurative paintings were tolerated for their academic value. But as soon as a naturalistic portrait art appeared all conversation seemed to turn to questions: Who is this person? Why should I care? How am I supposed to evaluate them? Other than nudging from professors, these critique questions were brought up with no discussion of the formal and technical attributes of the portrait paintings themselves; there was little discussion of their object value, let alone conceptual implications.

In her introduction of Portraiture, art historian Shearer West expounds on the paradoxical low status fine art portraits have received among professional artists, despite historically being considered only second, in genre, to historical paintings by the Royal Academies. "An emphasis on the need for the creative artist to invent and represent ideal images lingered from Renaissance art theory to the early 19th century and served to relegate portraiture to the level of a mechanical exercise, rather than a fine art." Furthermore, she points out how modernist experimentation led to the 20th century preference of abstraction over naturalism. Since the portrait art genre has traditionally been closely tied to ideas of realistic representation, contemporary portrait painting largely fell from favor (12-13). Traditional portraiture, which was so tied to likeness and the specificity of a subject, was too mimetic to be considered Art by modernist art critics (187). The few artists that continued to use the genre over the last century turned the practice on its head.

Literary critic Earnst van Alphen argues convincingly that as "the cherished cornerstone of bourgeois western culture," twentieth century portraiture liberated itself from the ideals of presence, essence, and "mimetic conceptions of representation" (Woodall 239-254). While van Alphen vehemently defends (thankfully) the contemporary relevance of figurative art, he concedes that the genre has changed significantly. Visual Artists working in portraiture such as Andy Warhol, Cindy Sherman, and Marlene Dumas have effectively undermined the authority of the bourgeois, divorced subjectivity from both artist and sitter, and modeled their objects as flaccid representations without origin or referenciality (242).

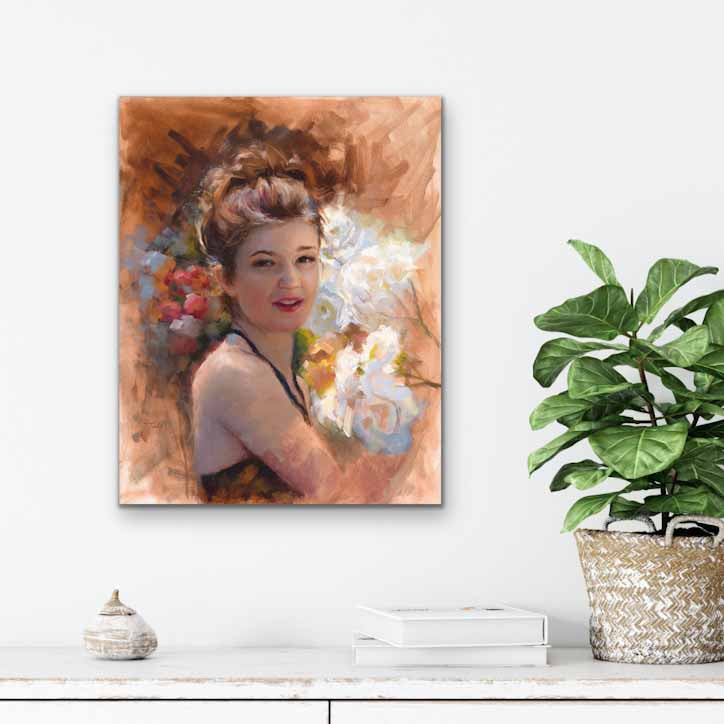

Of course, I knew nothing of art history or modernist prophecies pronouncing the death of traditional portrait portraiture when I chose to abandon graphic design and become a portrait painter. Thirteen years ago, I had a bare minimum of post-secondary education. I was a homeschooling mom of five children and my mind was blossoming under the rigors of educating my children. My husband and I had just moved to what we thought would be our forever home. As I watched my youngest son toddle around our yard and garden, a desire to paint his image burst within me. I purchased some cheap acrylic paints at the grocery store and started studio practice using my children's easel. This was a first step in a journey that would completely alter my life trajectory.

The passion to paint and see as an artist sustained me during those short happy years in our new home. It complemented the education I was giving my children. It helped me to differentiate myself outside of the role of wife and mother. It freed me from my claustrophobic conservative community and enabled me to meet new people. My passion broadened my perception, patience, and capacity to love. I felt born again. American author Henry Miller's charming account of his own painting journey echoes much of my own metamorphosis.

"I remember well the transformation which took place in me when I first began to view the world with the eyes of a painter. The most familiar things, objects which I had gazed at all my life, now became an unending source of wonder, and with wonder, of course, affection . . . Now as I studied the object's physiognomy, its texture, its way of speaking, I entered into its life, its history, its association . . . all of which only endeared it more" (17).

When crisis after crisis entered my life robbing me of all youthful hope, the search for beauty through painting became balm to my aching soul-a vital connection to the world outside my pain. I was already a portrait painter and art teacher when I had the opportunity to return to college. I was in for a big surprise.

The first art school critique of my modern portrait paintings made it apparent that accurately representing my subjects on canvas was not enough to engage academic viewers. While I'd had relative success engaging the sentimentality of a conservative audience, the contemporary art scene was a world apart. Professors educated during the sixties and seventies held on to the "common critical trope" rejecting "the importance of portraiture to modernist art (West 187). I received even more push-back from graduate students who felt representational portraits were "anachronistic, inert, [and] crusty - a form of vanity exclusive to the rich" (Patrovich).

A preposterous idea emerged from one of my fellow students. Perhaps I was too skilled, she insisted. Perhaps I was hiding weak concepts behind traditional painting techniques. Possibly equally preposterous, I adversely determined it was my lack of skill that prevented my portraits from speaking to a larger audience. I didn't know how to visually, let alone verbally, express the infinite value of the intuitive, almost magical process and raw emotion inherent in fine art portraits. How could I demonstrate the importance and relevance of the contemporary modern portrait artist in the age of the instant selfie?

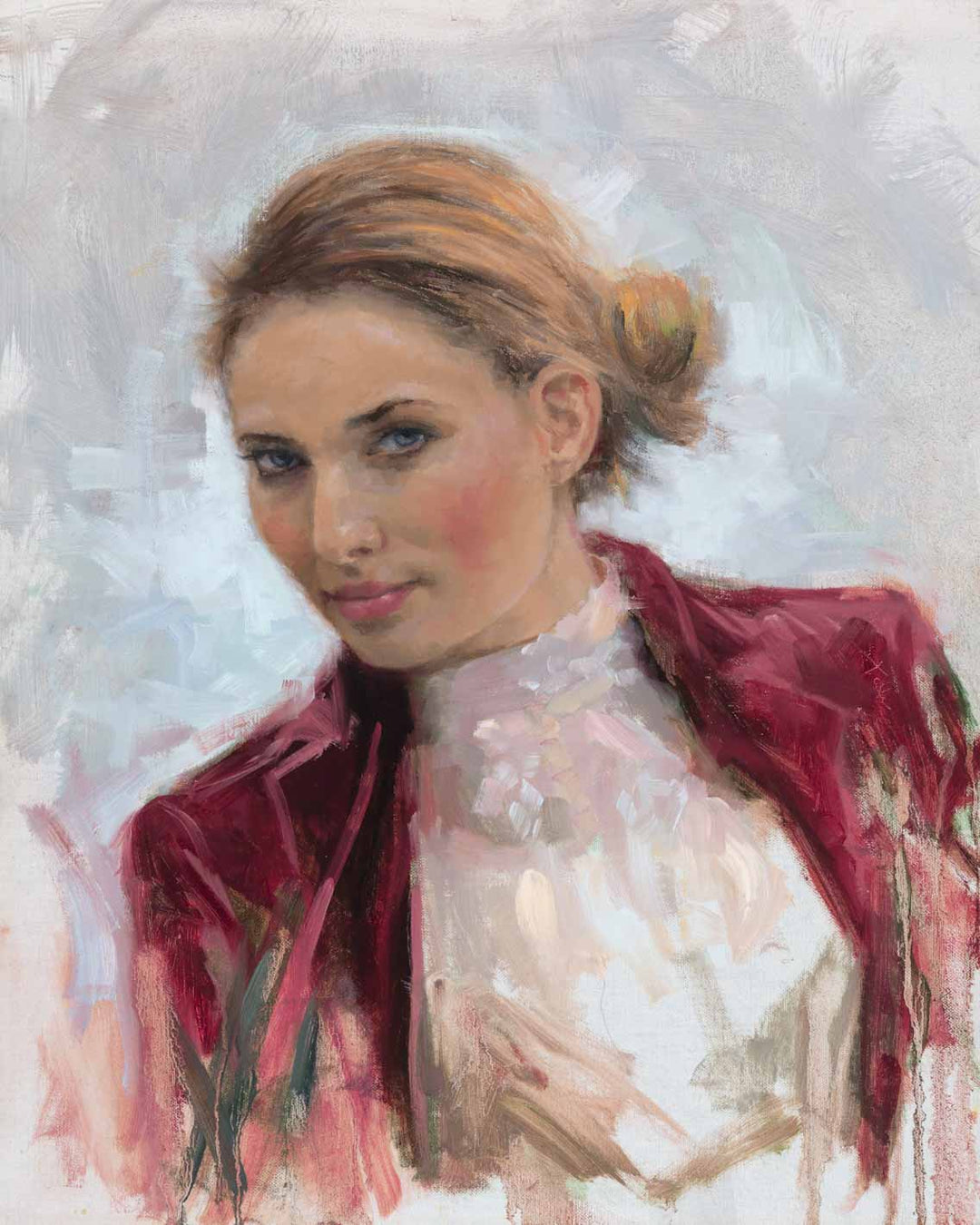

Don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater: portraiture survives

Despite predictions of its eventual demise, traditional figurative painting never really died, nor has it all been transformed beyond recognition. Twentieth century artists like Andrew Wyeth, Lucian Freud, and Alice Neel defied prevailing prejudices fostered by the avant-garde and continued to paint naturalistic portraits from live models. These post-war artists kept portraiture relevant by subverting only a few of the traditional conventions of portraiture. For the most part all three artists, despite their vast stylistic differences, abandoned flattery, traditional posing, and environmental identifiers of their sitter’s identity (West 39). These quiet trail blazers painted people of their own choosing, from their own community, a significant departure from the elitist concept of the commissioned portrait.

Artists devoted to keeping proven painting techniques alive doggedly remained at their easels passing on the tradition to a new generation. Of the contemporary artists to have made their mark in the last two decades British artist Jenny Saville stands out. Like the growing number of contemporary artists, she emphasizes the body rather than the face as a conceptual strategy for her larger-than-life portraits. Many of her earlier figurative paintings were designed to challenge impossible Western standards of beauty. Women depicted with emphasized sagging breasts, stretch-mark-laden folds of fat, and protruding purple veins lit in the most unflattering flat cool light are intended to “show us a body that is exactly the opposite of the eroticized and perfected models’ bodies . . . in glossy magazines” (West 214). However, the focus on the body and unflattering rendering of her subjects, stray a bit too far from the conceptions of identity that the portraiture genre encompasses.

Other prominent contemporary artists have recently emerged who hold on to the many innate strengths of traditional portrait painting. Kehinde Wiley is a notable example. Employing Renaissance painting techniques, historical poses and lush patterns reminiscent of Baroque European paintings, he diversifies and broadens the white-man-centric practice. His heroic paintings of black and brown people provide a needed scaffolding to update and remodel the portrait genre (Patrovich). Portland, Oregon artist Samantha Wall has also managed to embrace precision without sacrifice of subjectivity or beauty in her hyper-realistic drawings of interracial women. Unlike the maximalism of Wiley, Wall’s art calls attention to what is missing as much as what is present. Her meticulous yet, minimalistic approach emphasizes the human universality of facial expression (Wall).

The only way around is through

It was during the beginning second semester of my Junior year that Oregon College of Art and Craft (OCAC) announced its forthcoming closure. I was sitting in my therapist's office bemoaning a recent critique. Compounded stress put me on the brink of quitting my dream of getting my Bachelor of Fine Arts. My therapist was encouraging me to persevere when a notification popped up on my phone: "Oh Shit! The school is closing." I read the words from my schoolmate and breathed out a plethora of mixed feelings.

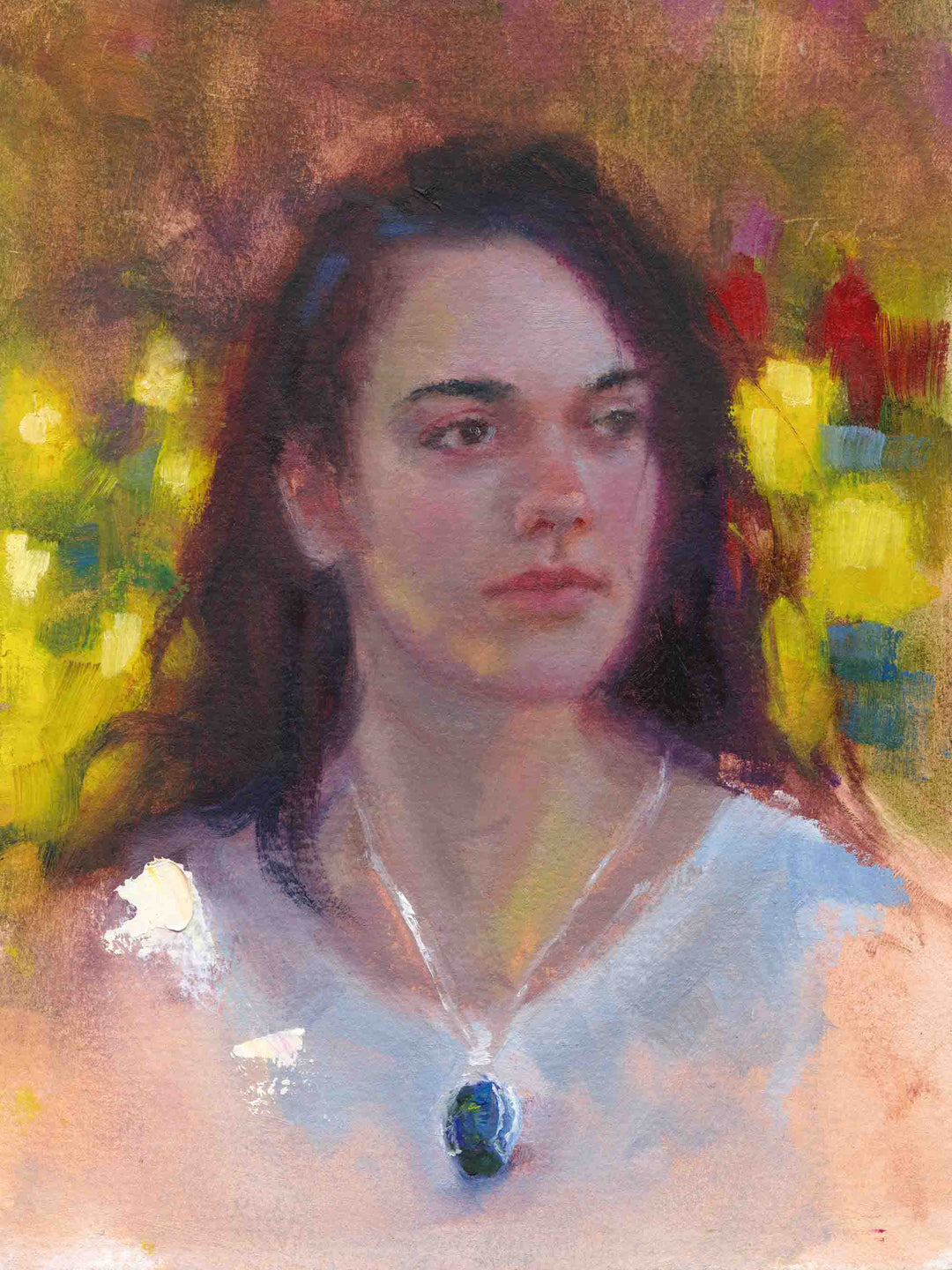

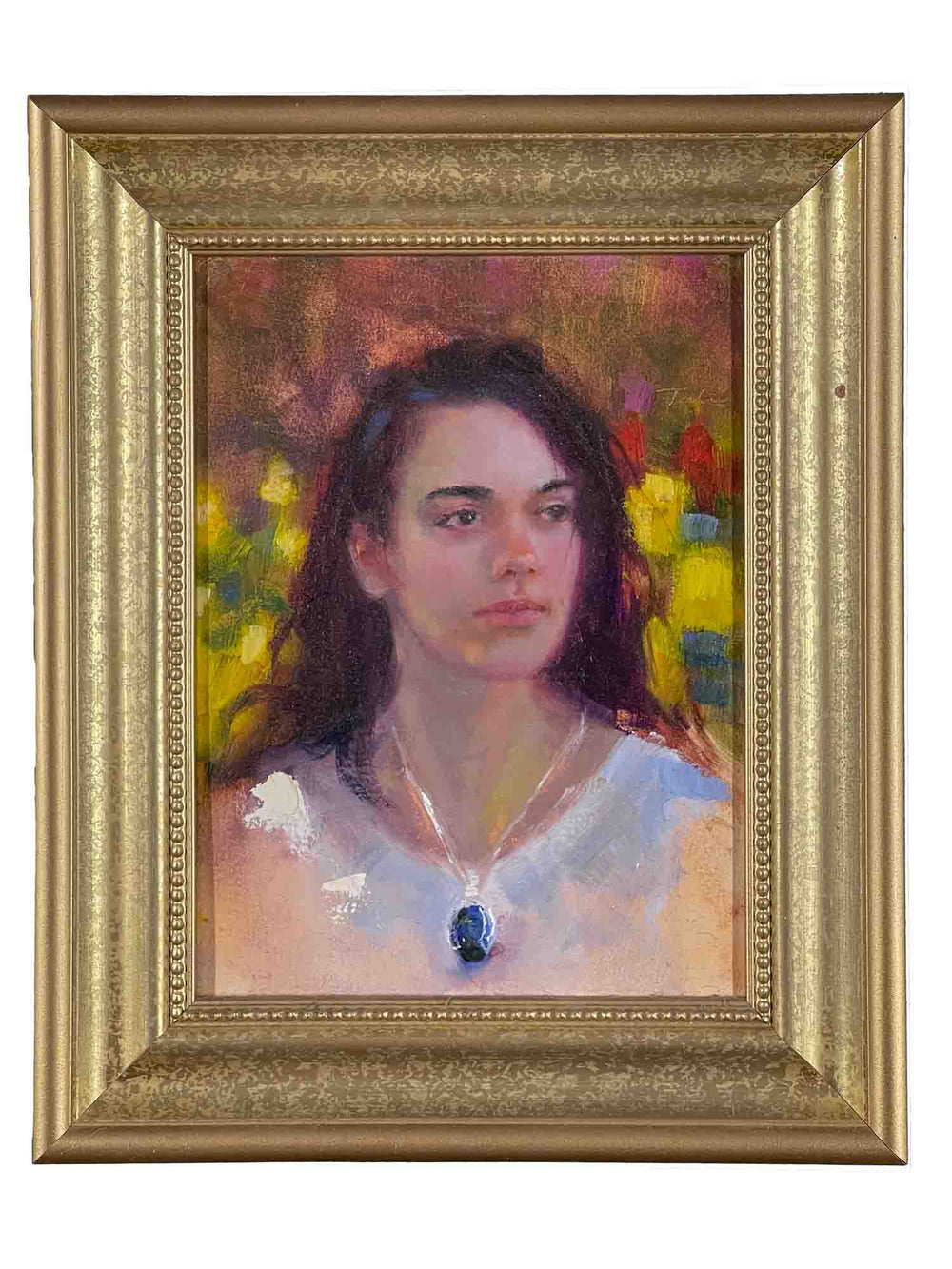

Throughout that last semester at the OCAC campus, I developed a closer relationship to my cohort and professors. The collective crisis brought down social and hierarchical boundaries between students, faculty, and staff. We clung together to face the unknown. We were being abandoned by the institution we trusted to see us through. I put my portrait painting aside to relieve some of the pressure of singularly defending the practice. Painting abstract landscapes from imagination provided a needed reprieve from conflict giving me more emotional strength to stay focused on my task at hand. However, I am not one to give up easily. During summer break I started researching the history of portraiture, hungry to better understand what I may have missed.

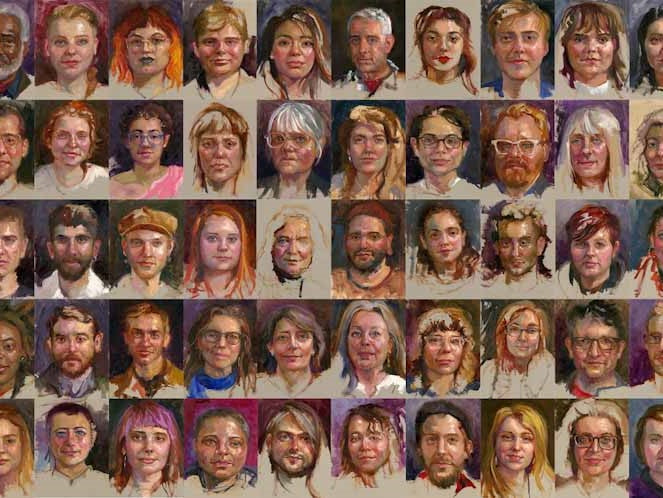

While sitting in the first class of the 2019/2020 semester, I looked around at my displaced OCAC cohort and realized I didn't really know all of them. In my struggle of going back to school, and my resistance to embrace contemporary art, I had somehow missed the opportunity of truly seeing the people who were sharing my path in higher education. Being a part of a society so enamored with digital socialization and communication, I had failed to look behind the screens, roles, and titles and truly experience the entirety of my unique position. Portraiture called me back, like a rubber band snapping back into position. For me, the quickest way to understanding is through observational painting. After a lot of researching, reading, and discussing, I found a few precedents for an idea that has been kicking around my head for several years.

Continued in part 2, precedent, process, and modern portrait painting technique

Works Cited

Miller, Henry. To Paint Is To Love Again. Cambria Books, 1960.

Patrovich, Dushko. "The New Face Of Portrait Painting". The New York Times, 2018, https://nyti.ms/2BUeLjs.

Wall, Samantha. “Indivisible.” SAMANTHA WALL, 2018, www.samanthawall.com/indivisible.html.

*West, Shearer. Portraiture. Oxford University Press, 2004.

*Woodall, Joanna. Portraiture: Facing The Subject. Manchester

Univ. Press, 2008.

Leave a comment