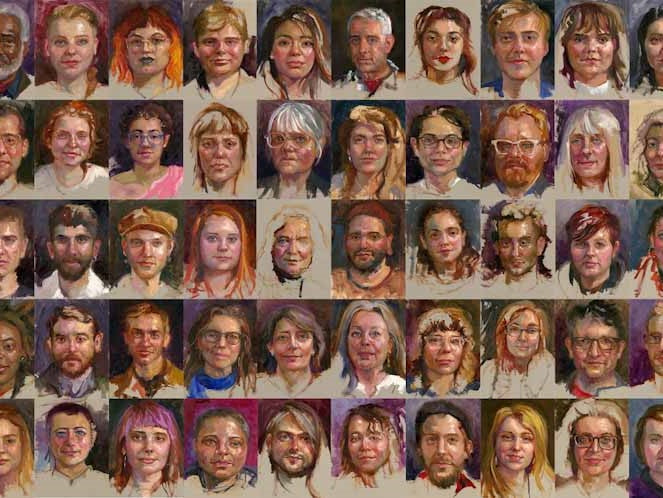

Continued from 51 Oil portraits from life: Community Remains part 2, precedent and process

The Eye of the Beholder

The type of seeing required to paint a likeness of a person is different from the ordinary perception people use when they go about their everyday activities. The slow, meditative looking necessary for observational drawing necessary in portraiture is difficult to describe to someone inexperienced in naturalistic representation or portrait drawing. Notable 19th century art history critic John Ruskin proposed that the painter's vision is akin to a sixth sense. "If a person who had no taste for drawing were to one day be endowed with both the taste and power, he would feel, on looking out upon nature, almost like a blind man who had just received his sight" (285).

I don't feel like I truly see a person, unless I've spent some time trying to find my subject's likeness. When brush and canvas aren't available or feasible, I paint their face in my mind asking myself questions, like how would I describe the shape of the mouth in the fewest brush strokes? Or where is that orange reflection on the face coming from? Which pigments would I mix to pin down that color?

My painter's perception is a whole brain and body activity, both cerebral and visceral—using my right brain creative side and left brain analytical side. When I look at my subject, my mind begins making calculations: proportions between a facial feature like the chin and eyebrow, large shape divisions of light and shadow, relationships between shapes and edges. My visual analysis must be made while my brush searches for gesture, essence and the manifestation of a form. If my mental visual calculations are more black-and-white in determining value and relationships, my color perception comes more from my gut. I feel out my color choices, almost like how my son approaches math; I guess and check. Some colors feel right, while others don't.

This sort of intuition is only tangentially related to eyesight but is certainly interdependent with vision as far as its broader definition of imagination toward the future. Pablo Picasso is famously said to have proclaimed that a painter doesn't even need eyesight at all in order to convey meaning: "Painting is a blind man's profession. He paints not what he sees, but what he feels, what he tells himself about what he has seen." Contemporary portrait artist John Bramblitt agrees, bringing in the perspective of a blind painter. "Many of the most interesting parts of a person are invisible and hidden from view anyway; I think my blindness might be just the lens that is needed to see into that world" (Chabas).

I have to deliberately toggle between two opposing perceptions in order to capture a person's likeness: seeing and intuiting. These senses are as different as looking at raindrops on a windshield and looking through raindrops on a windshield-I cannot do both at the same time. And this can make speaking and listening difficult. I cannot count how many times I found myself staring across the table at a friend and realizing I haven't heard a word they said, I was too busy painting their faces in my mind.

The actual crafting of the portrait is very much a part of my seeing as an artist. There is no certainty in what I'm seeing, until I carefully construct my subject's face on my canvas. Looking and crafting using my whole brain, however, doesn't fully describe my artist's way of seeing, or the sort of sixth sense poets and artists alike have attempted to embody in the limited vehicle of language. Something happens when I am busy describing in paint the living soul sitting three to four feet away from me. This something approaches transcendence. Henry Miller (1891-1980) called it love.

"To paint is to love again. It's only when we look with eyes of love that we see as the painter sees. His is a love, moreover, which is free of possessiveness. What the painter sees he is duty-bound to share. Usually he makes us see and feel what ordinarily we ignore or are immune to. His manner of approaching the world tells us, in effect, that nothing is vile or hideous, nothing is stale, flat and unpalatable unless it be our own power of vision. To see is not merely to look. One must look-see. See into and around" (17).

It is this latter description that likely comes the closest to this other perception I use while searching for a good likeness. To truly see is to love, and to love is to paint. Yet, I still find this description inadequate. There is something of an energy transfer or mingling that occurs while I paint my subject, particularly from life: touching without touching, seeing without seeing, knowing without knowing. I cannot force it to happen. I cannot predict when it will happen. Nor does it always happen. A few of my sitters even cried when it happened. And I cried when it didn't.

Here’s looking at you

In his essay "The Fayum Portrait Painters (1st-3rd century)," renown art critic John Berger considers the question of why these funerary Antique portraits painted between the 1st and 3rd centuries still "strike us today as being so immediate" (Berger, Portraits Ch. 2). He continues probing, asking why images painted of people living over two thousand years ago feel as individual and differentiated as we do, and how is it that they feel more contemporary than all the European art which followed them? Throughout the essay, Berger expounds on how and why these remarkable portraits were painted, their function far more complex than simple ritual. He turns the traditional gaze relationship up-side-down. "We should consider these works not as portraits, but as paintings about the experience of being looked at . . ." (Berger, Portraits Ch. 2). It is this precious nugget of truth that was most impactful to me during my own creative process, spending time with individuals that seemingly had little in common with me.

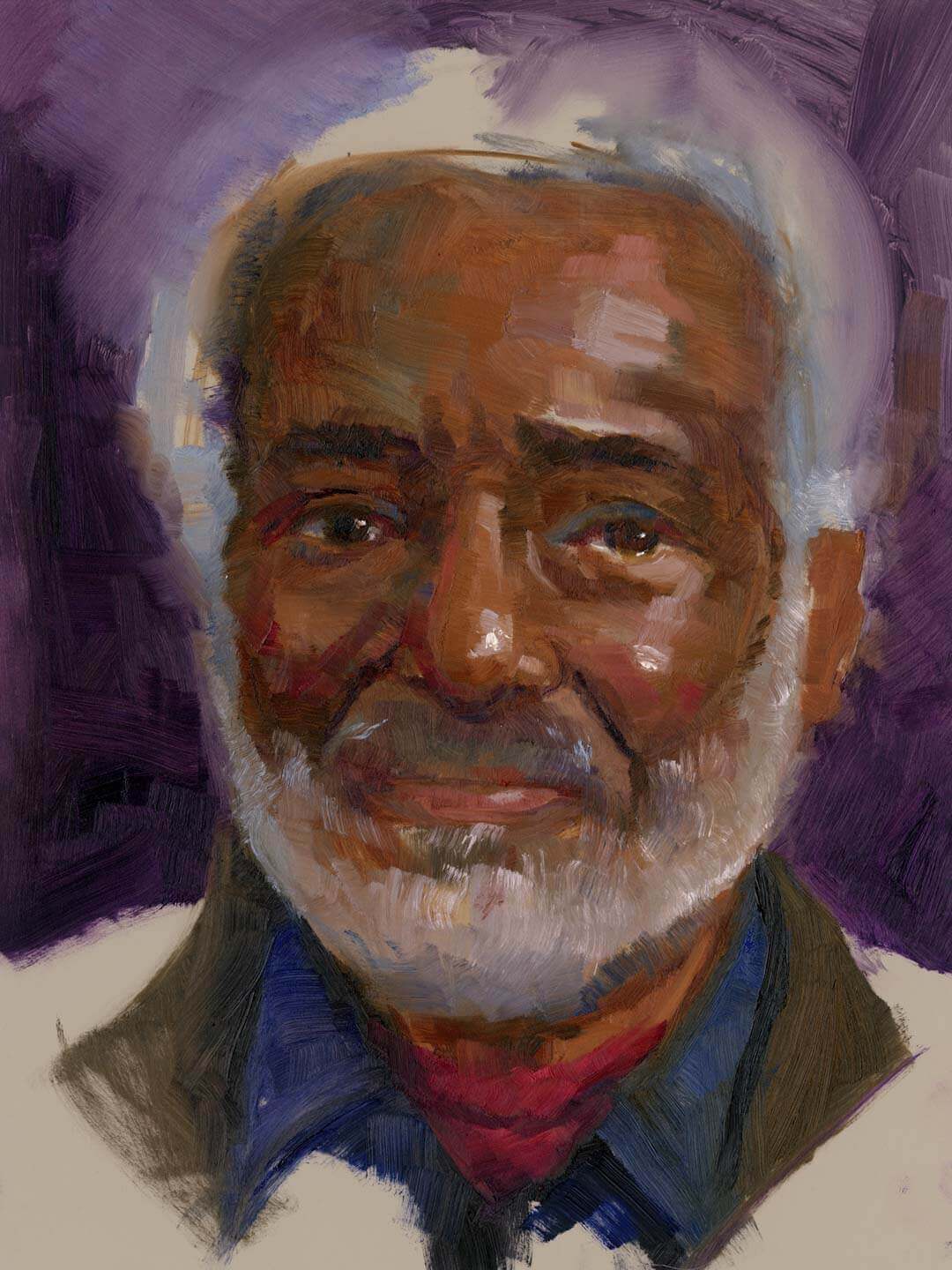

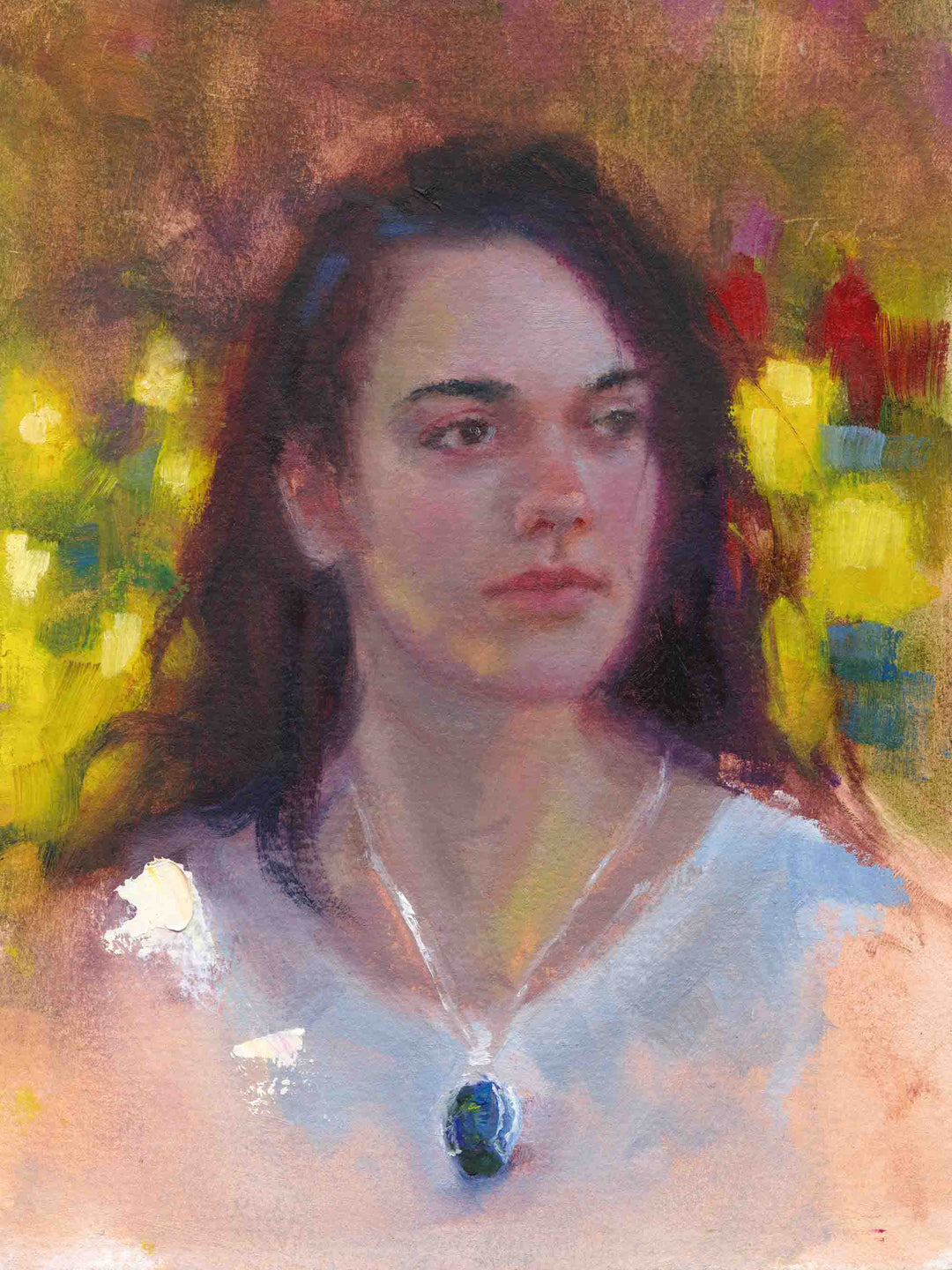

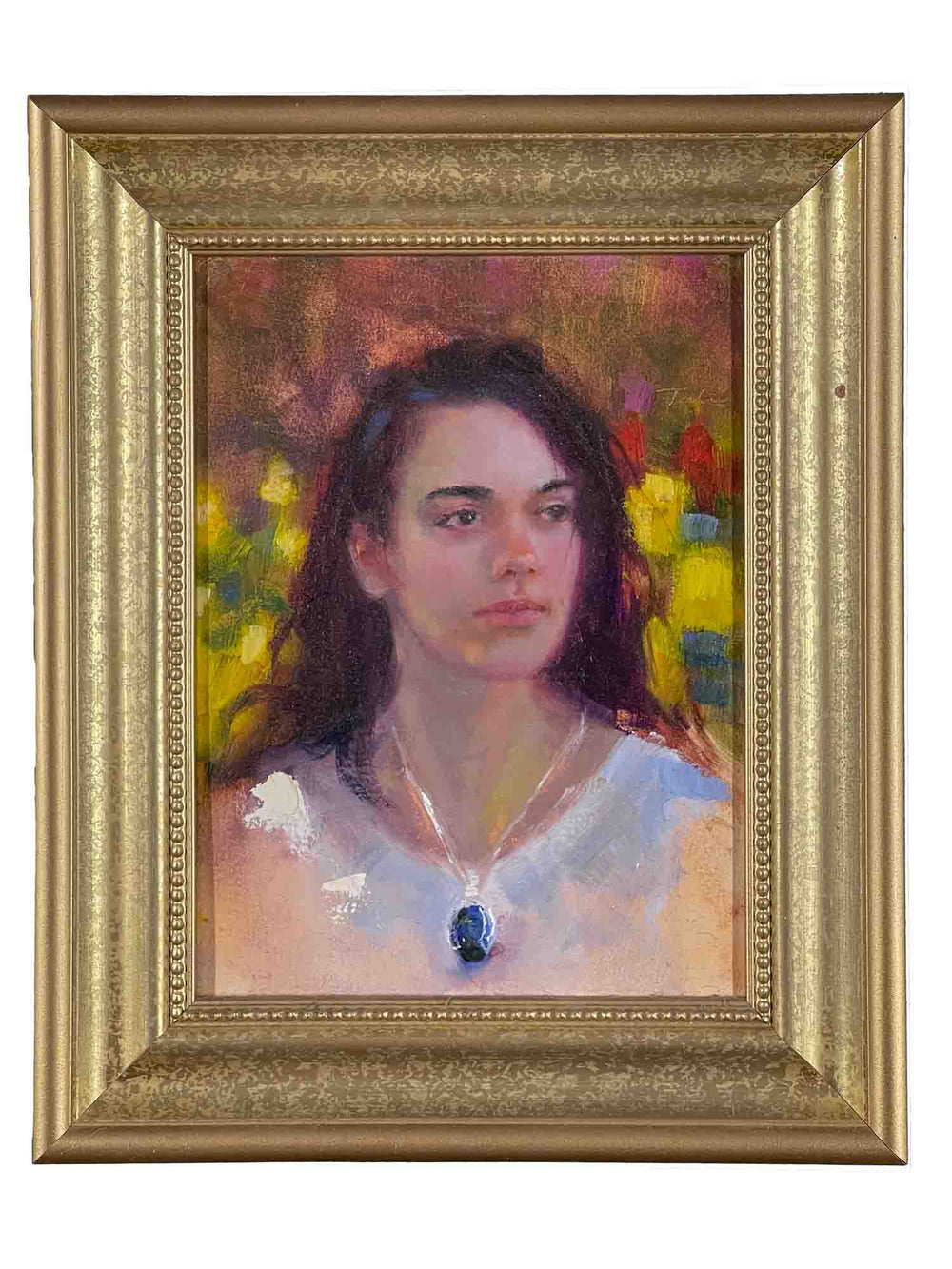

As I painted Emerson, I was overcome by our similarities. He, a sixty-something black man from the Deep South, and me a Caucasian forty-something art student from a Jewish Israeli Kibbutz. And yet for those brief two-hours I felt closer to him than my own siblings. He looked at me straight in the face, mourned with me for my losses, celebrated my successes, and shared his love of humanity that had grown within him throughout his difficult life. At times he was quiet, trying to control his composure. I felt no need to fill those sacred moments with words. I just kept painting and loving the beautiful man before me. He hugged me when he first came into my studio and I apologized for my emotional state. He hugged me when he left, after taking several moments to look deeply at his portrait. With real tears in his eyes he thanked me and left.

I checked my phone messages remembering the familiar ding that I almost hadn't heard during the spell of the moment.

"Rachel is free" the words read, accompanied by a broken heart emoji. I felt my heart sink into my gut.

The message was expected but utterly devastating. Thirteen-year-old Rachel had been fighting an aggressive brain cancer for the last two years. "Free" meant gone, gone from this world, gone from her family, violently ripped from her mother's arms, my best friend, who would never be the same again.

I looked back at Emerson's portrait. His painting looked back at me with compassion, almost tears in his eyes, and I knew I would not "adjust" his portrait any further. He would stay as he was, his life and compassion memorialized in paint-a cancer survivor himself who also lost a son he loved. Whenever I think of Rachel now, I also think of Emerson, and how he looked at me.

In the image of G-d

Looking at a person who is part of my community is not like looking at a stranger. It's already established we have something in common and depending on how often I've interacted with them, I have preconceived ideas of both their character and physical features.

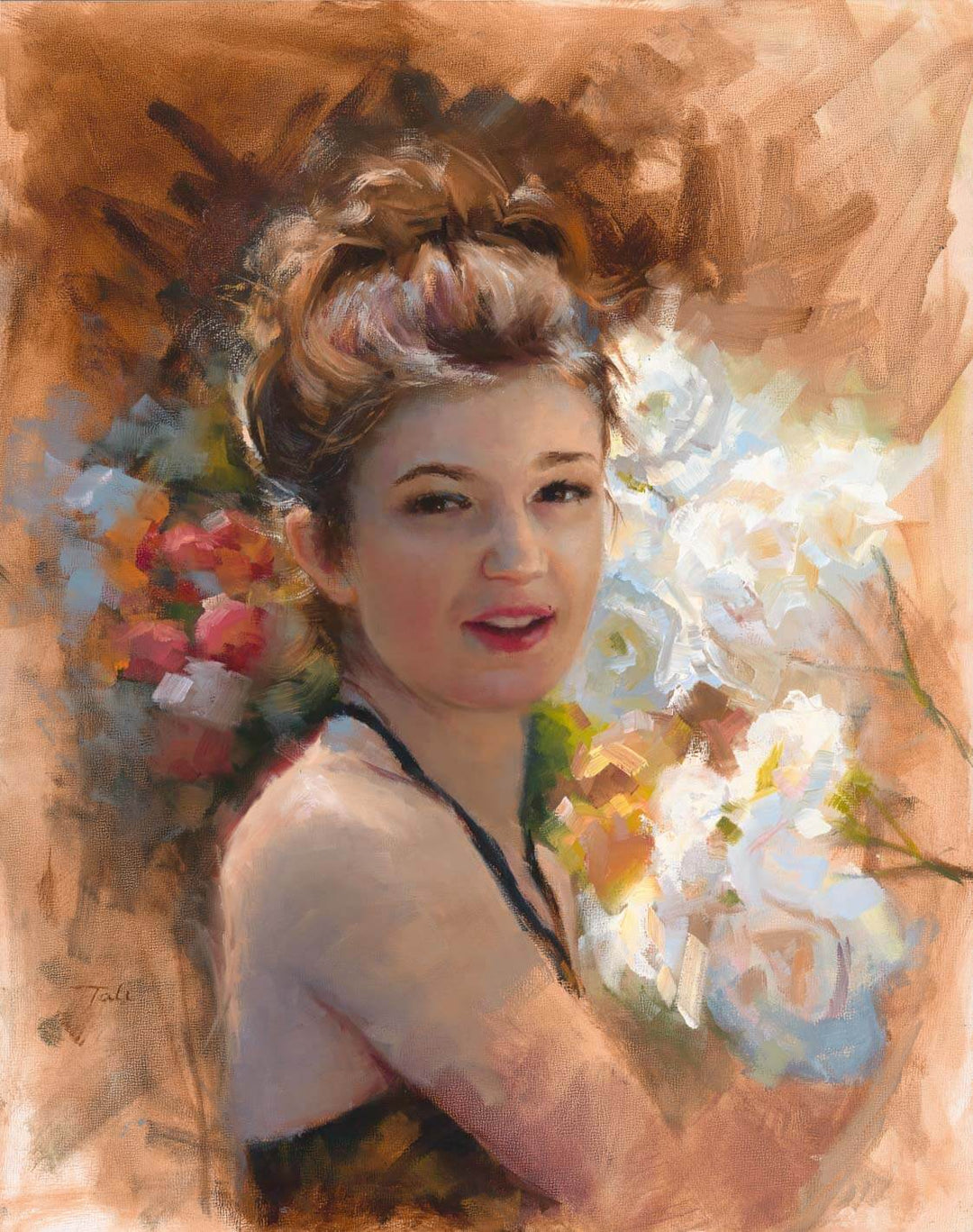

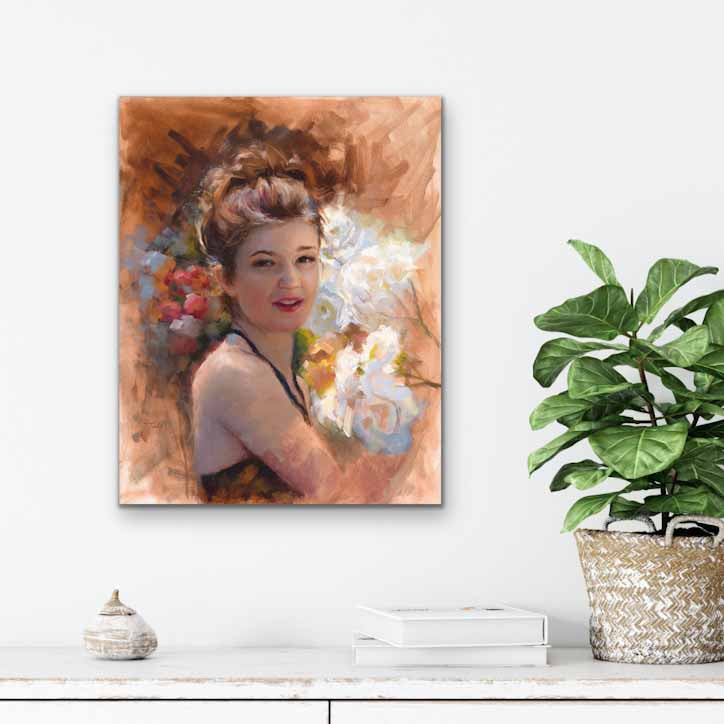

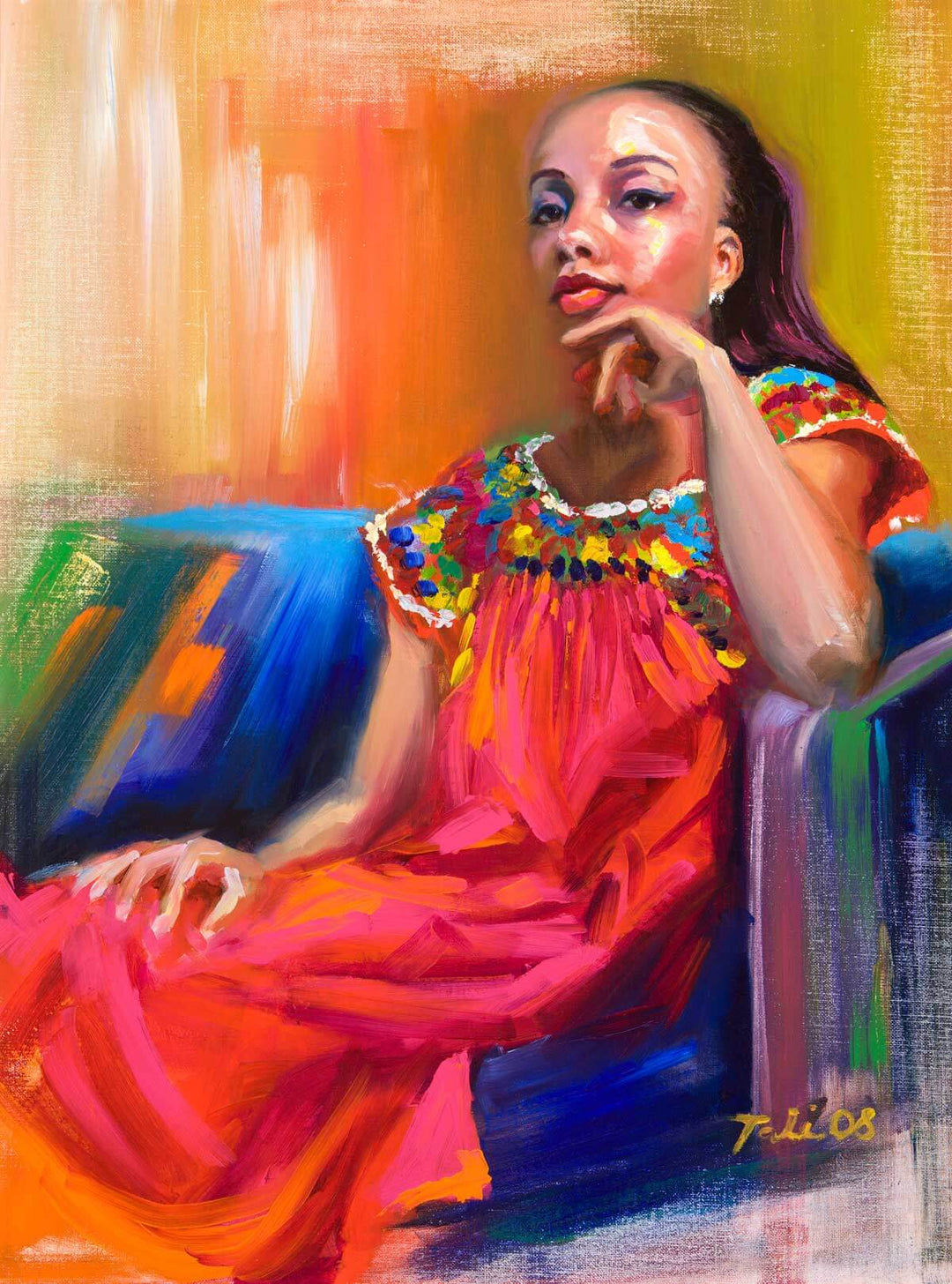

I didn't know Aubrey for very long when she first came into my studio to be painted. She was never in any of my classes; she hadn't hung out at the student lounge. In fact, when I first walked into Professional Practice class at the beginning of fall semester, I had no idea who she was. While that changed quickly as she shared her art and inspiration through various assignments, I was still surprised that she willingly signed up to be the first person to be painted.

In many ways, not knowing her well was to my advantage.

Preconceptions and assumptions can get in the way of direct observation. Master Artist David Leffel emphasizes that knowledge can easily interfere with the process of painting. "If you know how it's going to come out, what's the point of doing another painting" (Leffel). Leffel clarifies knowledge as based on secondhand experience and not related to the pursuit of understanding that painting from life offers.

Still, our relative unfamiliarity with each other made us both nervous.

It took me several moments stumbling around my studio to get things set up. I took a few photos of her first, wanting to have her picture on the iPad while I painted her from life. She was difficult to photograph, and I am no great photographer. Not only were the photos unflattering, but they didn't represent her delicate features or unique gestures.

To complicate matters even more, she was sitting two to three feet away from me, forcing an intimacy that is not present in most every-day interactions. This closeness was uncomfortable and distracting, for both of us I believe.

Aubrey wasn't just anyone, but someone who navigated through the same community and experienced the same abandonment by OCAC. More importantly, I learned early on that like me, she struggled with the academic resistance to beauty for its own sake. Also like me, she had a complicated relationship with her mother. And like me expressed an insecurity regarding her physical attributes. I wanted to paint her beautifully, as she deserved, adding another layer of pressure that never completely subsided even after painting forty-nine other people.

One of the reasons realistic modern portrait painting is challenging, particularly in our age dominated by photographic imagery, is that there is very little room for error, or even interpretation, when capturing likeness of a specific human being. If an eye painted a millimeter too large or small, or a nose is missing a certain bump or specific slope, the entire image can unravel into a portrait of someone else. A simple selfie provides the sitter and viewers a far more precise and culturally "reliable" representation of my subject. However, "likeness . . . is certainly a different thing from what a photograph gives, which may or may not present a very true sense of the subject" points out Oregon artist George Johanson in his book Equivalents, Portraits of 80 Oregon Artists. "One's physical image seems changeable . . . The closer and more carefully one looks, the more the face changes from one viewing to the next" (11).

It is precisely this difficulty that drives my interest in portrait painting. The slipperiness of likeness and its multi-faceted, ever changing parameters continue to tease me forward to reach for a greater depth of understanding of my human subject. "The stakes were high, the margin narrow. And in art these are conditions which make for energy" (Berger, Portraits Ch. 2).

Energy is a good word to describe my portrait of Aubrey. I spent most of the time chasing her features as she wiggled in her seat telling me her story. I remember lamenting in my mind that I would only have enough time for a monochromatic oil sketch, a sketch I wasn't even sure looked like the fluttering creature in front of me. If I could only catch her-capture her in paint.

I realize now, that this archaic desire is precisely what was initially interfering with our experience. One does not "capture" a likeness, pinning it down to a board like a collected butterfly. No, likeness is something that finds the artist. It is a gift.

Many portrait artists agree. "What a joy drawing is when it is going well!" exclaims George Johanson. "The hand takes over and moves almost with its own will . . . and it is as if you as the artist are almost a bystander" (10). Rose Frantzen whose charming children's portraits seem particularly alive also speaks of this gift, ". . . likeness is this thing I feel. Knowing when I've reached a point of likeness doesn't seem to come from my head; it comes from something a little lower, in the area of my chest. I begin to feel the person in the painting can breathe" (21). This gift of finding and drawing a portrait likeness became almost religious in nature-certainly mystical, but always reliable. The old biblical axiom came into play, "Faith without works is dead." My faith in the gift grew as portrait painting after portrait painting emerged with recognizable likeness, all I had to do was to keep working, looking and searching.

I would have vehemently argued with that sentiment only months ago. Likeness, I believed, was a matter of measured precision. There was no mystery, mysticism, or magic involved. It was numbers and shapes! While I have not abandoned the notion that painting the exterior skillfully and precisely, opens the door to the viewer perceiving the interiority or essence of my subject, I have abandoned art students the notion that expert technique is required for an emotive and valuable likeness (much to the collective sigh of relief from my professors).

Works Cited

Berger, John, and Tom Overton. Portraits - John Berger On Artists. 2015, ebook.

Chabas, Dorothée. "The Art Of Seeing With The Brain (About Sargy Mann And Other Blind Painters)". Dorothée Chabas, 2019, www.dorotheechabas.com/neuroesthetics-blog/the-art-of-seeing-with-the-brain-about-sargy-mann-and-other-blind-painters.

Frantzen, Rose. Portrait of Maquoketa. Old City Hall Press, 2009. Portrait of Maquoketa information and book available here.

Johanson, George. George Johanson, Equivalents: Portraits of 80 Oregon Artists. Portland Art Museum, 2001.

Miller, Henry. To Paint Is To Love Again. Cambria Books, 1960.

Ruskin, John. "Essay On The Relative Dignity Of The Studies Of

Painting And Music, And The Advantages To Be Derived From Their Pursuit". The Works Of John Ruskin, E. T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn, George Allen, London, 1903-1912, pp. 265-286, https://warburg.sas.ac.uk/pdf/cih1150b2210146v1.pdf. Accessed 18 Jan 2020.

To be continued in part 4

Leave a comment